Table of Contents

Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking by Malcolm Gladwell is a pivotal work that synthesises scientific research and anecdotal evidence to explore the profound impact of rapid, instinctive, and generally unconscious cognition on human decision-making. Published in 2005, the book’s central thesis challenges the long-standing Western cultural preference for exhaustive, time-consuming deliberation, arguing that choices made spontaneously—often within the “blink of an eye”—are frequently as sound as, or even superior to, those derived from painstaking analysis.

Gladwell, a journalist and staff writer for The New Yorker, aims to provide a popular readership with a counterintuitive glimpse into modern psychology’s revelations about inner mental life. The book is not merely a celebration of the power of the glance, but a detailed exploration of when to trust these rapid reactions, when to be wary of them, and how to cultivate and control this ability.

I. The Core Theory: Thin-Slicing and the Adaptive Unconscious

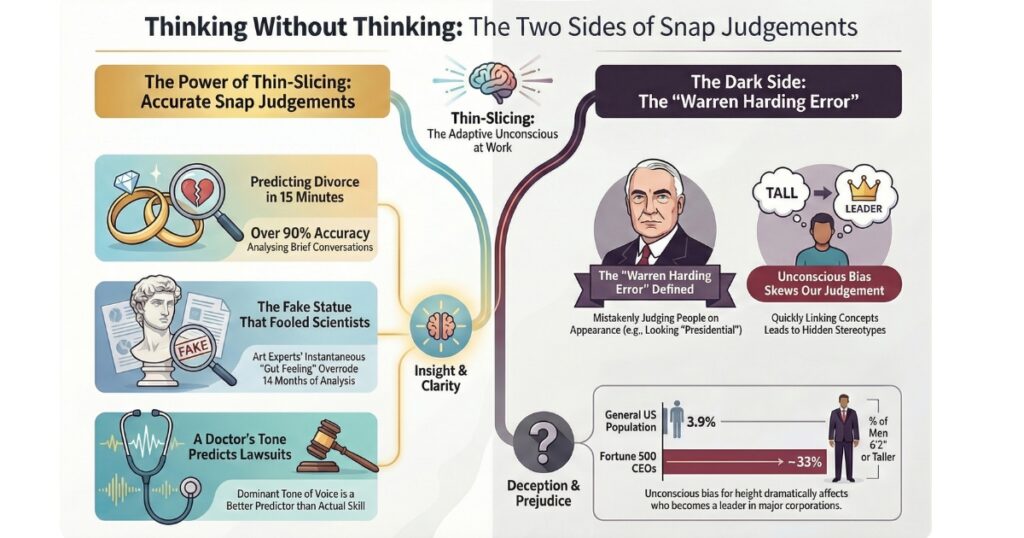

The fundamental mechanism driving rapid cognition is dubbed thin-slicing—the inherent human capacity to rapidly extract highly reliable patterns of information from tiny slivers of experience. This ability allows us to glean deep insight from minimal data, making quick judgments that can be remarkably accurate.

This process is powered by the adaptive unconscious, a mental system that functions as a massive, internal computer. This unconscious mechanism quickly and quietly processes vast amounts of information—all available knowledge—to instantly generate impressions and first judgments, far faster than our conscious minds can realize. This is Gladwell’s version of what some dual-process theorists term “fast thinking” or System 1 cognition. The adaptive unconscious is not the “dark and murky place” described by Freud, but rather an efficient, sophisticated mechanism essential for human functioning and survival, constantly sizing up the world, warning of danger, and initiating action.

The Triumph of Trained Intuition: Expertise and Frugality

A critical insight of Blink is that reliable thin-slicing is not a mystical gift, but a highly learned skill rooted in deep domain expertise and structured practice. Experts, having accumulated years of experience and a vast internal database of patterns, are uniquely capable of filtering out irrelevant “noise” to focus on the handful of factors that truly matter.

1. Connoisseurship and Pattern Recognition

The ability of trained intuition to surpass lengthy analysis is dramatically illustrated by the story of the Getty kouros, a purported ancient Greek statue. Despite 14 months of careful analysis by the Getty Museum’s geologists and lawyers, which concluded the statue was genuine, visiting art experts immediately felt an “intuitive repulsion”. Art historian Federico Zeri focused instinctively on the fingernails, and Thomas Hoving recalled his first thought: “fresh”—an inappropriate reaction to a two-thousand-year-old artifact. The intuitive reaction was correct; the statue was a forgery, proving that experts could glean more in two seconds than the museum team could in months of research.

Similarly, Gladwell presents examples like the ornithologist who can identify a rare bird in flight instantly by catching its “giss”—its essence—an ability born of extensive practice. Tennis coach Vic Braden could accurately predict a double-fault before the player’s racket made contact with the ball, relying on subtle, unspoken cues picked up instinctively.

2. The Power of Frugality: Less Is More

Blink forcefully argues that “less is often more” in decision-making, particularly when complex problems are reduced to their underlying essential factors. The sheer volume of information can actually lead to analysis paralysis, confusing or confounding decision-makers and impairing accuracy.

The example of doctor diagnosis in Emergency Rooms illustrates this principle. Traditionally, physicians gathered all available information to assess chest pain, leading to inconsistent and often inaccurate diagnoses. Cardiologist Lee Goldman developed an algorithm for heart attack diagnosis focusing on only three urgent risk factors (unstable angina, fluid in the lungs, systolic blood pressure below 100) combined with the ECG results. This minimal data approach proved to be substantially more accurate than the exhaustive, traditional method. The extra information, such as whether a patient smoked or had diabetes, was not only useless in the immediate diagnosis but actively harmful because it confused the doctors’ judgments.

3. Diagnostic Thin-Slicing: Marriage Prediction

The success of psychologist Dr. John Gottman in predicting divorce is a cornerstone of the book’s argument. By rigorously observing and coding the interactions of married couples (a process called SPAFF, for specific affect), Gottman developed a “marital DNA” or signature. He could watch a couple for just 15 minutes and predict with 90% accuracy whether they would still be together 15 years later.

Crucially, Gottman achieved this accuracy not by reviewing endless variables, but by focusing on his “Four Horsemen”: defensiveness, stonewalling, criticism, and, most powerfully, contempt. Contempt, expressed through eye-rolling, sarcasm, or hostility, is identified as the single greatest predictor of divorce because it conveys disgust and superiority, attacking the partner’s sense of self. This selective focus on high-signal variables confirms the power of thin-slicing to find the simple underlying patterns in complex phenomena.

II. The Pitfalls and Corruption of the Blink

While rapid cognition is powerful, Gladwell dedicates significant space to exploring its duality, stressing that the adaptive unconscious is fallible and susceptible to biases, stress, and external desires.

1. The Locked Door and the Storytelling Problem

A major philosophical challenge of thin-slicing is that the underlying machinations of our intuitive decisions remain inaccessible—a phenomenon Gladwell calls “The Locked Door”. Experts like Vic Braden cannot articulate how they know a double-fault is coming, nor could the Getty experts initially articulate why the kouros felt wrong.

This opacity leads to the “storytelling problem”: the human tendency to automatically construct plausible but entirely false assumptions to explain decisions we made unconsciously. When pressed for a rational explanation, we simply come up with what seems like the most plausible answer, even if it has no connection to the real, unconscious influences. This is why research often finds that asking direct questions about motivations (e.g., to speed-daters or married couples) provides few meaningful clues.

2. Cognitive Bias: The Warren Harding Error

When rapid cognition fails, it often fails due to unconscious prejudices and stereotypes. The Warren Harding Error describes the mistake of judging individuals based solely on superficial appearances. Harding, who possessed a commanding presence, handsome features, and “presidential” looks, was elected U.S. President despite his intellectual mediocrity and lack of distinguished political achievement.

This error demonstrates how physical traits, such as height, trigger powerful, positive unconscious associations. Similarly, Gladwell uses the Implicit Association Test (IAT) to reveal that individuals often hold “implicit” or unconscious attitudes—automatic associations regarding race, gender, or career—that contradict their stated conscious beliefs. This unconscious bias can translate into real-world behaviour, such as job applicants with “white-sounding” names receiving 50% more interview invitations than those with “black-sounding” names, even with similar qualifications. In the case of car sales, black and female shoppers were consistently quoted higher prices than white males, indicating that salesmen unconsciously stereotyped them as “lay-downs” (suckers).

3. Stress and Temporary Mind-Blindness

The ability to thin-slice effectively is severely impaired under conditions of extreme stress and high arousal, which Gladwell argues can lead to temporary mind-blindness—a loss of our natural capacity to read intentions and emotions.

The tragic 1999 shooting of Amadou Diallo by four NYPD officers serves as the primary case study. The officers, working under intense pressure in a dark, high-crime environment, misinterpreted Diallo’s actions (reaching for his wallet) as a mortal threat (reaching for a gun). Gladwell explains that extreme stress pushes the heart rate above 145 beats per minute, leading to a breakdown of complex motor skills and cognitive processing. The officers’ vision and thinking narrowed, causing them to cease reading Diallo’s face (which likely expressed terror) and instead rely on rigid, aggressive stereotypes of a “dangerous criminal”. The encounter was over in a matter of seconds, demonstrating that removing time subjects one to the lowest-quality intuitive reaction.

III. Action Steps for Decision Makers: Controlling the Blink

The most important lesson of Blink is that our snap judgments and first impressions are not immutable; they can be educated and controlled. Decision-makers can take active steps to shape and manage the environment and the training that influences their adaptive unconscious.

1. Cultivate Deep Domain Expertise

Since thin-slicing is built, not born, the primary action step is to acquire profound, domain-specific knowledge. This depth of experience allows experts to filter the few critical factors from irrelevant noise, making their snap judgments exceptionally reliable.

- Systematic Practice and Analysis: Experts should formalise their “gut feel” through structured analysis. For instance, food tasters use detailed lexicons (like the DOD scale for difference) to articulate and verify their subjective sensory experiences, transforming simple intuition into resilient knowledge.

- Case Exposure: Managerial training, such as case-oriented MBA curricula, should be viewed as a crucial method for developing the rapid pattern recognition necessary for thin-slicing in business, allowing future leaders to build their internal database.

2. Embrace Frugality and Structured Spontaneity

Decision-makers must overcome the Western bias that complexity and time equal quality. The optimal strategy requires balancing deliberate and instinctive thinking.

- Filter Irrelevant Data: Recognize that more information can be detrimental. In critical situations, simplify the task by focusing only on the essential factors (like the Goldman Algorithm) to avoid being muddled by excess data.

- Create Structure for Spontaneity: In high-stakes, fast-moving environments (like the battlefield or the ER), structure can enable spontaneity. Leaders, like General Paul Van Riper, should provide clear intent but avoid overburdening subordinates with endless process or information, allowing them the freedom to execute based on rapid cognition.

3. Neutralise Bias by Controlling the Environment

Decision-makers must be vigilant against the Warren Harding Error and the implicit biases held by their adaptive unconscious.

- Introduce “Screens”: The classical music world’s use of blind auditions (screens) demonstrated that removing visual cues (gender, appearance) immediately eliminated ingrained biases, leading to fairer and more accurate hiring decisions based purely on talent. In high-stakes assessment, removing potentially biasing visual information (if safe and feasible) can protect the integrity of the first impression.

- Conscious Override and Inoculation: Consciously intervening to counter bias is necessary. Gladwell notes that actively exposing oneself to positive examples of a minority group (e.g., thinking of Martin Luther King or watching the Olympics) can temporarily alter subconscious attitudes revealed by the IAT. In high-stress fields like policing, continuous training and simulation (stress inoculation) can help officers operate in the optimal range of arousal, mitigating the risk of temporary mind-blindness.

4. Interpret First Impressions (Beware of the New and Different)

When assessing novelty, decision-makers must interpret first impressions rather than taking them at face value. Initial negative reactions may stem not from genuine dislike, but from unfamiliarity.

- Contextualize Research: Consumer research is often unreliable for predicting preferences for groundbreaking products (like the Aeron chair or Kenna’s unconventional music) because people struggle to explain their reactions to the unusual or simply misinterpret their feelings. The initial feeling of “hate” might just be a proxy for “different”.

- Sensation Transference: Recognise that people do not evaluate products in isolation. Branding, packaging, and context influence the sensory experience (Sensation Transference). The failure of New Coke, for example, lay in ignoring the profound, positive unconscious associations consumers had with the established Coke brand and packaging, which were vital components of the “taste” experience.

IV. Conclusion and Critical Perspective

Blink successfully introduces the general public to the psychological study of rapid cognition, asserting that instantaneous judgments—the sophisticated output of the adaptive unconscious—can possess “as much value in the blink of an eye as in months of rational analysis”. Gladwell’s goal is to prompt a reevaluation of non-conscious thought and encourage better integration of instinct and deliberation.

However, the book has drawn academic criticism, primarily for its journalistic style and conceptual oversimplification. Critics argue that the book is a series of “loosely connected anecdotes… poor in analysis”, and sometimes inappropriately conflates distinct psychological phenomena under the blanket term “rapid cognition”. Furthermore, Gladwell is occasionally accused of presenting strong conclusions without engaging with contradictory scientific literature. Notably, his treatment of Paul Ekman’s universal facial expression claims in Blink appears to contradict his later work, reflecting the difficulty of synthesizing complex and evolving scientific fields.

Despite these critiques, Blink‘s enduring legacy lies in compelling leaders and individuals to understand that the quality of a decision is not directly proportional to the time spent making it. The book offers an essential framework for identifying when to harness the remarkable efficiency of trained intuition and when to impose deliberate structure to mitigate its inherent vulnerabilities, ultimately advocating for a balanced decision portfolio.

V. Action Steps for Decision Makers:

| Action Step | Focus Area | Detailed Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cultivate Deep Expertise | Intuition Quality | Dedicate time to structured exposure and practice within your domain to build the internal pattern database essential for reliable thin-slicing. |

| 2. Embrace Frugality and Edit Information | Decision Efficiency | Actively filter out irrelevant data (noise) to focus only on the few critical factors needed for a snap judgment (the signal), preventing “analysis paralysis”. |

| 3. Impose Structure on Spontaneity | High-Speed Decisions | For fast-moving situations, set clear, high-level intent (the mission) while empowering subordinates to use their rapid cognition and initiative in execution, avoiding excessive internal communication. |

| 4. Neutralise Implicit Bias | Fairness and Objectivity | Use structured mechanisms (e.g., blind evaluation “screens” or algorithms) to remove irrelevant visual or demographic cues, ensuring judgments are based purely on merit and performance. |

| 5. Train for Stress | Performance Under Pressure | Use training, simulations, and conscious practice (stress inoculation) to improve functional capacity under high arousal, mitigating the risk of temporary mind-blindness and irrational, aggressive reactions. |

| 6. Question Rationalisations | Self-Awareness | Be wary when someone—especially yourself—provides a detailed, confident explanation for an instinctive decision. Recognise the “storytelling problem” and that the stated reason is often merely plausible, not true. |

| 7. Interpret Novelty | Product/Idea Assessment | If initial reactions to a truly new product or idea are negative, distinguish between genuine failure (ugly) and simple unfamiliarity (different). Allow time and context for judgments to adjust before scrapping groundbreaking concepts. |

| 8. Consciously Override Bias | Ethical Judgments | Actively expose your adaptive unconscious to positive examples of groups toward which you hold implicit biases, thereby shifting unconscious associations to align with your conscious ethical values. |

Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking explores the profound impact of rapid, instinctive, and generally unconscious cognition on human decision-making. The book’s central thesis asserts that choices made spontaneously—in the “blink of an eye”—are frequently as sound as, or even superior to, those derived from painstaking, time-consuming deliberation.

The core concept is thin-slicing, defined as the inherent human capacity to extract significant and reliable patterns from a minimal amount of experience. This rapid thought process is driven by the adaptive unconscious, a sophisticated internal “giant computer” that instantly processes vast amounts of accumulated data to generate impressions and judgments far faster than conscious thought allows. This mechanism acts as an efficient system essential for survival and decision efficiency.

VI. Key Takeaways on Decision Making

1. Expertise is the Precondition for Reliable Intuition: Reliable thin-slicing is not an innate gift but a highly learned skill rooted in deep domain expertise and structured practice. Experts leverage years of accumulated patterns to filter out irrelevant information, making their snap judgments exceptionally reliable. For instance, psychologist Dr. John Gottman achieves 90% accuracy in predicting divorce by focusing exclusively on high-signal variables like contempt—an illustration of filtering out noise to identify the few factors that truly matter.

2. Frugality Often Outperforms Analysis: Gladwell argues that “less is often more”. Too much information can be detrimental, leading to analysis paralysis. The minimal-data approach is effective, as demonstrated by the Goldman Algorithm used for heart attack diagnoses, which proved more accurate than traditional exhaustive methods by focusing only on essential risk factors.

3. The Pitfalls of Bias and Stress: The adaptive unconscious is highly susceptible to cognitive biases and stereotypes. The Warren Harding Error illustrates how superficial appearance (such as looking “presidential”) can overwhelm rational assessment. Furthermore, the ability to thin-slice is severely impaired under conditions of extreme stress. High arousal can cause cognitive breakdown and “temporary mind-blindness,” leading decision-makers to rely on rigid, aggressive stereotypes rather than accurate perception, as seen in the tragic case of Amadou Diallo.

4. The Locked Door and Rationalization: Since the mental processes driving snap decisions remain inaccessible (the “Locked Door”), individuals frequently face the “storytelling problem”—automatically constructing plausible, yet false, explanations for actions driven by unconscious influences.

VII. Action Steps for Decision Makers

Decision-makers can educate and control their instincts:

- Cultivate Deep Expertise: Invest in structured exposure and practice to build a robust internal database for reliable pattern recognition.

- Neutralise Bias: Implement structured mechanisms like blind assessments (screens) to remove biasing visual cues (e.g., race, gender) and ensure judgments are based purely on merit.

- Embrace Structure for Spontaneity: In fast-moving situations, set clear, high-level intent while resisting the urge to overburden subordinates with excessive information, thereby enabling rapid cognition and improvisation.

- Interpret Novelty: Be wary of initial negative reactions to groundbreaking ideas, as “hate” may simply be a proxy for unfamiliarity.

- Consciously Override Bias: Actively expose the adaptive unconscious to positive examples of groups toward which biases are held, aligning unconscious attitudes with conscious ethical values.