Table of Contents

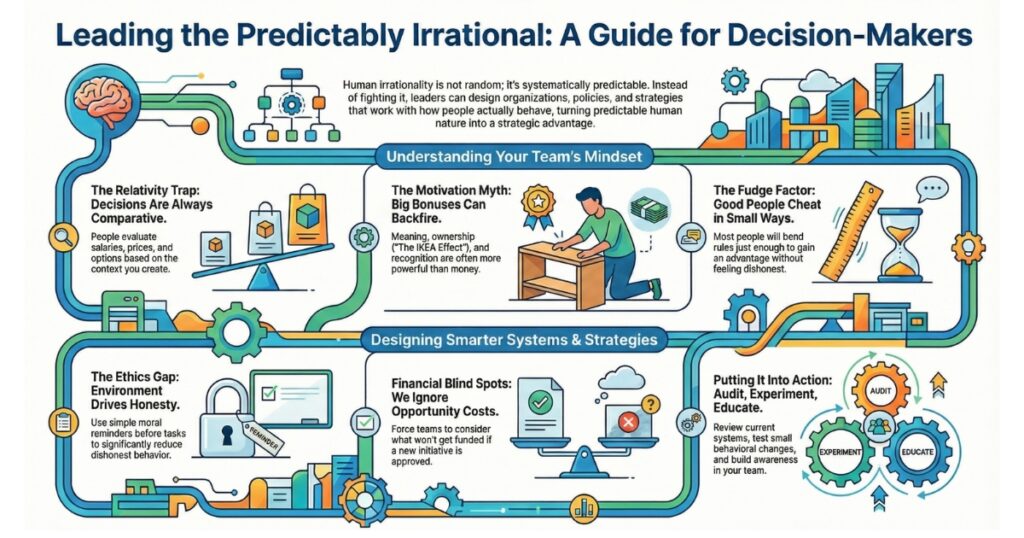

As a decision-maker, you face a fundamental challenge every day: the people you lead, the customers you serve, and even you yourself don’t behave according to the rational models taught in business school. Understanding this gap between theoretical rationality and actual human behavior isn’t just an academic exercise—it’s the difference between strategies that succeed and those that fail despite perfect logic.

Dan Ariely, one of the world’s leading behavioral economists, has spent decades uncovering a profound truth: human irrationality isn’t random chaos. It’s systematically predictable. And if you can predict it, you can design for it.

This insight transforms how we should approach leadership, organizational design, compensation strategies, and change management. Let’s explore how Ariely’s research across eight groundbreaking books can reshape your approach to decision-making and help you lead more effectively.

The Relativity Trap: Why Context Drives Your Team’s Decisions

One of Ariely’s foundational insights is that people rarely evaluate options in absolute terms. Instead, we’re wired to make comparative judgments. This has enormous implications for how you structure choices within your organization.

Consider compensation. An employee doesn’t evaluate their salary against some abstract measure of fairness—they compare it to their colleagues, to previous years, and to market benchmarks you provide. This comparative framework means that a well-structured compensation system isn’t just about the numbers; it’s about managing the comparison points.

The same principle applies to product pricing, vendor negotiations, and even how you present strategic options to your board. The way you frame alternatives fundamentally shapes which option appears most attractive. Marketers have long understood this through decoy pricing—offering three options where the middle choice is designed to make the premium option look reasonable by comparison.

As a leader, you can leverage this understanding in positive ways. When presenting budget proposals, the options you include create the frame of reference. When restructuring teams, the alternatives you discuss shape how people perceive the final decision. The key is to be intentional about the comparative context you create.

Ariely also identifies what he calls the Cost of Zero Cost—our irrational attraction to anything free. This explains why free shipping can drive purchasing decisions even when the total cost is higher, and why employees may prioritize free perks over more valuable benefits they must partially fund. When designing incentive programs or vendor relationships, recognize that “free” carries psychological weight far beyond its monetary value.

Motivation: Why Throwing Money at Problems Often Backfires

Perhaps no area of Ariely’s research matters more to leaders than his work on motivation. Traditional management theory suggests a simple equation: more pay equals more motivation equals better performance. Ariely’s experiments demonstrate this is dangerously wrong.

In studies examining high-stakes financial incentives for cognitive tasks, Ariely found that beyond a certain threshold, more money actually decreased performance. The pressure created by enormous bonuses triggered stress responses that impaired judgment and creativity. This has direct implications for executive compensation structures, sales incentive programs, and project-based bonuses.

This doesn’t mean money is irrelevant—it means it’s not the primary driver of sustained excellence. What truly motivates people is far more nuanced:

Meaning and purpose sit at the foundation of intrinsic motivation. When people understand how their work contributes to something larger than themselves, they invest more energy and creativity. As a decision-maker, your role isn’t just to assign tasks but to connect those tasks to meaningful outcomes. The administrative assistant isn’t just scheduling meetings—they’re enabling critical decisions that shape the company’s future. Frame it that way.

The IKEA Effect reveals that we value things more when we’ve invested effort in creating them. This has profound implications for change management and employee engagement. When you involve people in designing solutions rather than imposing pre-made answers, they become invested in the outcome’s success. Participation creates ownership.

Recognition emerges as a powerful motivator, often more impactful than monetary bonuses. But not all recognition is equal. Public acknowledgment, specific feedback about the value someone created, and visible appreciation from leadership carry weight. Generic praise emails do not.

Perhaps most critically, Ariely’s research reveals the danger of mixing social norms with market norms. When you introduce explicit financial transactions into relationships built on goodwill and community, you can destroy the intrinsic motivation that was driving generous contributions. The colleague who happily stayed late to help a team member may balk at mandatory overtime pay because you’ve transformed a favor into a transaction.

This insight should reshape how you think about company culture. Building an environment where people help each other, share knowledge, and go the extra mile isn’t about monetary incentives—it’s about fostering social bonds and shared purpose. When you try to “pay” for these behaviors, you may actually reduce them.

The Ethics Gap: Why Good People Make Bad Choices

Every organization faces ethical challenges, and most decision-makers believe their employees are fundamentally honest. Ariely’s research suggests this is both true and misleading. Most people are honest, but they’re also predictably dishonest in small ways.

The Fudge Factor represents the psychological space where people cheat just enough to gain advantage but not enough to shatter their self-image as ethical individuals. An employee might pad their expense report slightly, take office supplies home, or stretch the truth in a sales pitch—all while genuinely believing they’re honest people.

Several factors amplify this tendency. When the object of dishonesty is non-monetary—like stealing time, supplies, or data rather than cash—people feel less psychological resistance. When people are creative and good at rationalization, they’re better at constructing justifications for questionable behavior. And when everyone else seems to be bending the rules, social proof makes dishonesty feel acceptable.

As a leader, this research suggests that preventing ethical lapses isn’t primarily about stronger penalties or more surveillance. It’s about environmental design.

Moral reminders work remarkably well. Simple interventions like having people sign ethics statements before (not after) submitting expense reports, posting the company’s values in decision-making spaces, or beginning meetings with a brief acknowledgment of ethical standards can significantly reduce dishonest behavior.

Remove ambiguity. The more room for interpretation in your policies, the more space for rationalization. Clear, specific guidelines make it harder for people to convince themselves that questionable behavior is acceptable.

Make the abstract concrete. When consequences feel distant or abstract, ethical constraints weaken. Help people see the real impact of their choices—not through fear tactics, but through clear connections between actions and outcomes.

Model the behavior you expect. If leadership cuts corners or treats rules as flexible, everyone else will too. Your ethical choices set the organizational standard.

Financial Decision-Making: The Hidden Biases in Your Budget

While Ariely’s insights apply broadly, his research on financial decision-making speaks directly to core leadership responsibilities around resource allocation, pricing strategy, and investment decisions.

Opportunity cost blindness is perhaps the most expensive bias affecting organizational decisions. When evaluating whether to spend money on a new initiative, software platform, or marketing campaign, decision-makers naturally focus on whether the purchase is worth the price. What we systematically fail to consider is what else we could do with those resources.

This isn’t mere oversight—it’s a fundamental feature of how our minds process financial decisions. The solution isn’t just trying harder to remember opportunity costs. It’s building evaluation processes that force explicit consideration of alternatives. Before approving significant expenditures, require proponents to identify what won’t be funded if this initiative proceeds.

Mental accounting explains why organizations—and the people in them—treat money differently depending on its source or category. Marketing budgets get spent differently than operations budgets, even when the money could serve the company better if reallocated. Windfall revenues from unexpected sources get treated differently than steady earned income, often with less scrutiny.

Recognizing these patterns allows you to design better financial governance. Consider whether your budget categories create artificial constraints that prevent optimal resource allocation. Ask whether “found money” receives appropriate strategic oversight rather than being treated as free to spend loosely.

The pain of paying influences everything from how you structure customer transactions to how you implement employee programs. Payment methods that reduce the psychological discomfort of spending—like credit cards, automatic renewals, or company expense accounts—predictably lead to higher spending. This isn’t good or bad in itself, but it’s a reality you need to factor into financial planning and control systems.

For customer-facing decisions, reducing payment friction can increase sales but may also increase returns or buyer’s remorse. For internal controls, recognizing that corporate cards feel different than cash can help you design more effective spending policies.

Belief Formation: Leading Through Misinformation and Change Resistance

Ariely’s most recent research on misbelief offers crucial insights for leaders navigating organizational change, market disruptions, or internal resistance to new strategies.

The Funnel of Misbelief describes how rational people come to hold irrational beliefs through a predictable progression. It begins with an emotional component—stress, fear, or a lack of understanding that creates psychological discomfort. This emotional state generates a powerful need for explanations, even if those explanations don’t withstand scrutiny.

Next come cognitive biases, particularly confirmation bias and motivated reasoning. People seek information that confirms their emerging beliefs and discount contradictory evidence. Finally, social components reinforce the beliefs as people find community with others who share their views.

This framework explains why organizational change often meets unexpected resistance that seems immune to logical argument. It’s not that your team is being deliberately obstinate—they’re experiencing the emotional discomfort of uncertainty, filling that void with explanations that make sense to them, and finding validation in conversations with similarly concerned colleagues.

Effective change management requires addressing all three components:

Address the emotional root. Before presenting logic and data, acknowledge the stress and uncertainty people feel. Create psychological safety where concerns can be voiced. Provide understanding even as you work toward new outcomes.

Provide clear, consistent information early. Cognitive biases flourish in information vacuums. When people don’t understand what’s happening or why, they fill gaps with speculation. Transparent, frequent communication—even when you don’t have all the answers—reduces the space for unfounded beliefs to take root.

Leverage social components positively. If misbelief spreads through social reinforcement, truth must spread the same way. Identify respected voices within your organization who understand and support the direction you’re heading. Empower them to engage in peer-to-peer conversations. Create forums where people can discuss concerns and work through resistance together.

Don’t dismiss concerns as irrational. Even when objections to your strategy seem based on misunderstanding, treating them dismissively entrenches resistance. Engage seriously with concerns, explain your reasoning, and adjust where feedback reveals genuine issues.

Designing for Humanity: Your Strategic Advantage

The common thread through all of Ariely’s research is that human behavior, while predictably irrational, can be shaped through thoughtful environmental design. This is your opportunity as a leader.

Most organizations are designed around the assumption that people will behave rationally if given proper information and incentives. When behavior doesn’t match predictions, the response is typically to add more information or stronger incentives. Ariely’s work suggests a fundamentally different approach: design your organization, policies, and strategies around how people actually behave, not how economic theory says they should behave.

This means:

Structure choices to guide better decisions. Default options, simplified menus, and well-designed comparison points can steer people toward beneficial outcomes without restricting freedom.

Build meaning into work. Connect tasks to purpose, enable ownership through participation, and recognize contributions in ways that matter.

Create ethical environments. Use moral reminders, remove ambiguity, and model the behavior you expect rather than relying solely on punishment to prevent misconduct.

Account for financial biases. Force consideration of opportunity costs, watch for mental accounting distortions, and recognize how payment methods influence spending behavior.

Lead through the psychology of belief. Address emotional needs, provide clear information, and leverage social dynamics when navigating change.

The leaders who will thrive in an increasingly complex business environment aren’t those who can compute the most rational strategy. They’re those who understand that perfect rationality is impossible and design accordingly. They’re those who recognize that the human element isn’t a bug in the system—it’s the system itself.

Putting Insight into Action

Understanding behavioral economics intellectually is one thing. Implementing it is another. Start with three concrete steps:

First, audit your current systems through a behavioral lens. Where are you assuming rationality that doesn’t exist? Where are incentive structures potentially counterproductive? Where does your organizational design fight against human nature rather than working with it?

Second, run small experiments. Behavioral economics is fundamentally empirical. Test different approaches to presenting choices, structuring incentives, or communicating change. Measure results. Learn from what works in your specific context.

Third, build behavioral awareness into your leadership team. The insights from Ariely’s research shouldn’t live with one person or department. They should inform how your entire leadership approaches decision-making, strategy, and culture.

The ultimate message from Dan Ariely’s decades of research is one of pragmatic optimism. We’re all predictably irrational, but predictability means we can design for it. As a decision-maker, your role isn’t to eliminate human irrationality—it’s to understand it, account for it, and build organizations where people’s actual psychology aligns with successful outcomes.

That’s not just good behavioral science. It’s good leadership.