Table of Contents

In an age where decision-making has become increasingly complex, Richard H. Thaler, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, and Cass R. Sunstein, a legal scholar, have produced a groundbreaking work that fundamentally challenges how we think about choices, policy, and human behavior. “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness” introduces the concept of libertarian paternalism—an approach that preserves freedom of choice while gently steering people toward better decisions. This seemingly paradoxical philosophy has profound implications for leaders, entrepreneurs, policymakers, and anyone responsible for designing systems where people make choices.

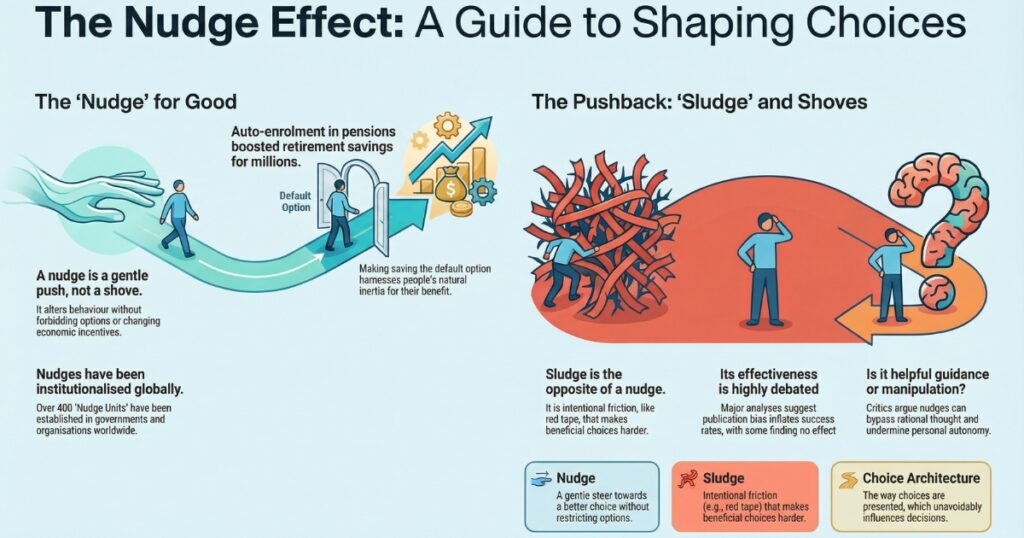

The book’s core premise is elegantly simple yet revolutionary: small changes in how choices are presented can have dramatic impacts on the decisions people make, without restricting their freedom. Unlike traditional paternalism, which imposes choices on people, or pure libertarianism, which assumes people always make optimal decisions on their own, libertarian paternalism recognizes that humans are predictably irrational and can benefit from thoughtful “choice architecture”—the design of environments in which people make decisions.

Why This Book Matters for Decision Makers

For business leaders and entrepreneurs, understanding the principles in “Nudge” is no longer optional—it’s essential. The book reveals why employees don’t enroll in retirement plans despite generous employer matches, why customers make poor purchasing decisions, and why even the most intelligent people fall prey to systematic errors in judgment. More importantly, it provides actionable strategies for improving outcomes without resorting to mandates or restrictions.

The relevance of this work extends across every sector. Whether you’re designing a healthcare plan for employees, creating a user interface for a digital product, organizing a workplace cafeteria, or developing public policy, the insights from “Nudge” can dramatically improve results. The book demonstrates that seemingly trivial details—like the default settings on a form or the order in which options are presented—can determine whether initiatives succeed or fail.

Since its publication, the concepts in “Nudge” have influenced governments worldwide. The United Kingdom established a “Nudge Unit” (officially the Behavioural Insights Team), and similar groups have emerged in the United States, Australia, and other countries. Major corporations have adopted these principles to improve employee benefits, customer experiences, and organizational effectiveness. The 2017 Nobel Prize in Economics awarded to Thaler validated the profound importance of behavioral economics in understanding real-world decision-making.

Understanding Humans Versus Econs

The foundational insight of “Nudge” distinguishes between two types of decision-makers. “Econs,” as the authors call them, are the rational actors assumed by traditional economic theory. These mythical beings have unlimited cognitive abilities, perfect self-control, and make decisions that consistently serve their best interests. They think like Albert Einstein, have the memory capacity of a supercomputer, and exercise the willpower of Gandhi.

In contrast, “Humans”—actual people—are busy, prone to errors, influenced by context, and often make decisions they later regret. Humans rely on two systems of thinking: the Automatic System, which is fast, instinctive, and often emotional; and the Reflective System, which is deliberate, rational, and requires effort. The Automatic System gets us through daily life efficiently but is vulnerable to systematic biases. Think of it as Homer Simpson versus Mr. Spock—both reside within us, but Homer often takes control.

The authors identify numerous mental shortcuts and biases that affect human decision-making. Anchoring causes us to be unduly influenced by the first number we hear, even if it’s arbitrary. The availability bias leads us to overestimate risks we can easily recall while underestimating less memorable dangers. Status quo bias creates powerful inertia, causing people to stick with whatever option requires the least effort. Loss aversion makes us hate losses roughly twice as much as we enjoy equivalent gains, leading to irrational resistance to change.

These aren’t occasional lapses—they’re predictable patterns that shape behavior across populations. Understanding these biases allows choice architects to design better systems that account for human nature rather than fighting against it.

The Power of Choice Architecture

The authors introduce the concept of the “choice architect”—anyone who organizes the context in which people make decisions. This includes employers designing benefit plans, government officials creating policies, doctors presenting treatment options, and parents describing educational choices to children. Even a cafeteria director arranging food displays is a choice architect, whether she realizes it or not.

The crucial insight is that neutral design is impossible. Every choice environment has an architecture, whether intentional or accidental. The order in which options appear, the default settings, the complexity of alternatives—all these factors influence behavior. Since some architecture is inevitable, the question becomes: should we design choice environments carefully to help people make better decisions, or should we pretend neutrality is possible and design haphazardly?

Thaler and Sunstein argue persuasively for intentional, thoughtful design while preserving freedom. Their “libertarian” principle insists that people should be free to do what they like and opt out of arrangements if they choose. The “paternalistic” aspect acknowledges that choice architects can legitimately try to influence behavior in directions that make people better off, as judged by themselves. This combination—preserving freedom while gently steering people toward better choices—defines the nudge approach.

The power of this framework is demonstrated through compelling real-world examples. When the Dutch authorities etched the image of a fly into airport urinals, they reduced spillage by 80 percent—men naturally aimed at the target without being forced to do so. When companies switched from requiring employees to opt in to retirement plans to automatically enrolling them with an opt-out option, participation rates jumped from around 60 percent to over 90 percent. These simple nudges produced dramatic results while maintaining complete freedom of choice.

Practical Applications Across Domains

The book systematically applies these principles across multiple domains, demonstrating both the versatility and power of nudges. In retirement savings, the authors detail how automatic enrollment, the “Save More Tomorrow” program (which allows people to commit to increasing savings rates with future pay raises), and better default investment options can dramatically improve financial security without forcing anyone to save.

In healthcare, they examine the complexities of the Medicare Part D prescription drug program, showing how poor choice architecture left seniors confused and making suboptimal decisions among dozens of plans. Better defaults, simplified information (through what they call “RECAP”—Record, Evaluate, and Compare Alternative Prices), and intelligent assignment systems could save money and improve health outcomes.

For credit markets, including mortgages, student loans, and credit cards, the book reveals how confusing terms and hidden fees exploit human limitations. Requiring clear disclosure in standardized formats would enable meaningful comparison shopping and protect vulnerable consumers without restricting access to credit.

Environmental protection provides another compelling application. Rather than relying solely on command-and-control regulations or assuming people will voluntarily reduce consumption, smart nudges like making energy usage visible through devices like the Ambient Orb (which glows red when consumption is high) can reduce energy use by 40 percent. The “Don’t Mess with Texas” anti-littering campaign succeeded by tapping into Texas pride and social norms, reducing litter by 72 percent in six years.

The authors also tackle controversial topics like organ donation, arguing that presumed consent (where people are donors by default but can easily opt out) would save thousands of lives annually while fully preserving individual choice. They even propose privatizing marriage—having the state recognize only civil unions while allowing religious and private organizations to define marriage as they wish—as a way to resolve contentious debates while maximizing freedom.

Main Practical Lessons for Leaders and Entrepreneurs

1. Design Default Options Carefully and Transparently

Default rules are among the most powerful nudges available, yet they’re often chosen arbitrarily or with ulterior motives. Leaders should recognize that whatever happens when someone does nothing becomes the default, and large numbers of people will end up with that option through inertia alone. The key is selecting defaults that serve users’ interests rather than the organization’s convenience.

For employee benefits, automatic enrollment in retirement plans with appropriate default contribution rates and investment allocations can dramatically improve financial security. The authors recommend starting with at least a three percent contribution rate that automatically increases over time, paired with diversified, low-fee index funds as the default investment. Research consistently shows that automatic enrollment increases participation from around 60 percent to over 90 percent, with minimal opt-out rates.

For consumer products, default settings should reflect what most users want most of the time, not what generates the most revenue. Software companies that default to sending marketing emails or sharing user data may boost short-term metrics but ultimately erode trust. Similarly, subscription services that default to automatic renewal should make cancellation genuinely easy, not hidden behind multiple screens and confirmation steps.

The critical principle is transparency. Defaults should never be secret or manipulative. Organizations should be willing and able to publicly defend their choice of defaults. If you wouldn’t want customers or employees to know why you chose a particular default, that’s a sign you’ve crossed the line from helpful nudge to harmful manipulation.

2. Reduce Complexity and Provide Meaningful Information

Humans struggle with complex decisions, especially when they’re infrequent and lack clear feedback. The Medicare Part D example illustrates this painfully—seniors faced with choosing among 40 to 60 prescription drug plans, each with multiple variables, typically made poor decisions or avoided choosing altogether. Even sophisticated people find it overwhelmingly difficult to optimize across dozens of dimensions.

Leaders should therefore simplify wherever possible. Offer a small set of well-designed options for most users, with the ability to access more complex choices for sophisticated users who want them. For retirement plans, this might mean a default balanced fund, three to five lifestyle funds (conservative, moderate, aggressive), and a full menu of individual funds only for those who actively want to construct custom portfolios.

When complexity is unavoidable, provide tools that make choices comprehensible. The RECAP principle—requiring providers to disclose complete information in standardized, machine-readable formats—enables meaningful comparison. Credit card companies should send annual statements showing all fees and interest paid. Mortgage lenders should provide standardized summaries enabling easy comparison of total costs. Healthcare plans should offer personalized recommendations based on actual medical needs and prescription history.

The goal is helping people translate abstract information into terms they understand. Instead of telling someone a car gets 28 miles per gallon, show them it will cost approximately 1,200 dollars per year in fuel at current prices. Rather than listing megapixels on cameras, explain what size prints each model can produce. Map choices to actual experiences and outcomes people care about.

3. Expect Error and Design Forgiving Systems

Traditional economic theory assumes people make optimal decisions. Reality demands that we expect errors and design systems that minimize their consequences. The best example is the gas tank cap attached by a piece of plastic—a ten-cent solution to a common problem that costs drivers time and money. Yet for years, automakers built cars with detachable caps despite knowing people routinely drove away without them.

Organizations should systematically identify common errors in their systems and implement safeguards. Digital cameras that originally lacked any indication that a photo was taken now include a satisfying click sound. Cars buzz if you don’t fasten your seatbelt and turn off headlights automatically to prevent dead batteries. Gmail prompts you if you mention an attachment but don’t include one. These simple interventions prevent predictable mistakes.

For high-stakes decisions, build in cooling-off periods or confirmation steps. Door-to-door sales regulations require a three-day cancellation window because people often make impulsive purchases they later regret. Similar logic applies to major life decisions like marriage or divorce—mandatory waiting periods ensure people don’t act on temporary emotional states. In business contexts, important transactions might require a 24-hour confirmation period or approval by a second person.

The key is anticipating where human limitations will cause problems and removing obstacles to better choices. Cafeterias can place healthy foods at eye level and make them easier to grab. Retirement plan administrators can send reminders before enrollment deadlines and make forms available at the point of decision. Buildings can locate bathrooms and stairways to encourage movement and chance encounters.

4. Leverage Social Influence Strategically

People are deeply influenced by what others do and what they believe others think is right. This creates powerful opportunities for positive nudges but also risks of harmful conformity. Leaders should understand that social norms act as invisible forces shaping behavior throughout organizations and markets.

Research shows that telling people “most of your neighbors conserve energy” reduces electricity consumption more effectively than providing cost information or appealing to environmental values. Informing taxpayers that “more than 90 percent of Minnesotans pay their taxes in full and on time” increases compliance more than threats of audits or explanations of how tax dollars are spent. Hotels can increase towel reuse by noting that “most guests in this room” reused their towels.

However, social influence can backfire if misused. Telling people that underage drinking is widespread actually increases drinking by normalizing it. Similarly, emphasizing how many people cheat on taxes or litter creates a descriptive norm that encourages the negative behavior. The solution is highlighting positive norms while avoiding suggestions that bad behavior is common.

Organizations can leverage social influence by making good choices visible and celebrated. Public recognition of employees who enroll in wellness programs or save appropriately for retirement creates peer pressure in positive directions. Showing people how their energy use or charitable giving compares to similar others motivates improvement. Creating opportunities for employees to influence each other—through mentoring, team challenges, or social networks—harnesses conformity productively.

5. Frame Choices to Reflect True Costs and Benefits

How options are presented profoundly affects decisions, often in ways people don’t recognize. The identical surgery outcomes described as “90 percent of patients alive after five years” versus “10 percent dead after five years” generate dramatically different choices, even though the information is logically equivalent. Framing matters.

Leaders should frame choices in ways that help people appreciate real consequences. Credit card companies might be required to show: “If you pay only the minimum, you will pay X dollars in interest over Y years.” Energy bills could display: “You used 25 percent more energy than efficient households like yours.” Retirement projections might show: “At your current savings rate, you’re on track for a retirement income of X dollars per month,” accompanied by images of the lifestyle that income would support.

The goal isn’t manipulation but clarity. Framing should illuminate rather than obscure. When people have difficulty understanding complex information, translating it into concrete terms helps them make informed choices. Mortgage lenders should show total interest paid over the life of the loan, not just monthly payments. Retirement plans should project actual income available in retirement, not just account balances. Food labels should translate serving sizes into terms people actually use.

Loss framing often proves more motivating than gain framing because of loss aversion. “If you don’t insulate your home, you will lose 350 dollars per year” motivates more than “If you insulate, you will save 350 dollars per year.” Leaders should consider how loss framing might increase engagement without being manipulative. The key is ensuring the framing accurately represents reality rather than distorting it.

6. Use Incentives Wisely While Recognizing Their Limitations

Traditional economics focuses heavily on incentives—pricing, rewards, and penalties that change the cost-benefit calculus of decisions. These remain important, but behavioral insights reveal their limitations. For incentives to work, people must notice them, understand them, and factor them appropriately into decisions. Salience matters as much as size.

The authors propose making incentives more visible and immediate. Energy bills that show real-time costs would motivate conservation more effectively than monthly summaries. Thermostats that display hourly costs of heating or cooling create salient feedback. Exercise equipment that shows calories burned in terms of food equivalents (ten minutes equals one cookie) makes abstract measures concrete and motivating.

Financial incentives work best when combined with smart choice architecture. The “dollar a day” program for teenage mothers—paying one dollar for each day they avoid getting pregnant again—costs little but creates a recurring salient reminder. Stickk.com allows people to put money at stake toward goals, with funds going to charity (or even to organizations they hate) if they fail. These approaches combine material incentives with behavioral insights about salience, loss aversion, and commitment devices.

For employee benefits, incentives should align with organizational goals while accounting for human behavior. Matching contributions to retirement accounts provide powerful incentives, but they only work if employees enroll and understand the match. Similarly, health insurance copays aim to reduce unnecessary utilization, but they also discourage preventive care and medication compliance that would save money long-term. Incentive design must consider not just how Econs would respond but how actual Humans will behave.

7. Implement Feedback Systems That Drive Learning

People improve performance when they receive clear, immediate feedback. Digital cameras allow photographers to see results instantly and adjust, unlike film cameras that delayed feedback by days or weeks. Good choice architecture includes feedback mechanisms that help people learn and self-correct.

Organizations should create systems that make consequences visible. Retirement plan statements should show not just current balances but projected retirement income based on current contribution rates, with comparisons to recommended targets. Credit card statements should prominently display year-to-date fees and interest paid. Energy utilities should provide comparisons to similar households and trend information showing whether consumption is increasing or decreasing.

Feedback works best when it’s personal, specific, and actionable. Generic advice to “save more” or “use less energy” rarely changes behavior. Telling someone “you saved 15 percent more than last month” or “your current contributions will provide approximately 2,400 dollars per month in retirement, which is 30 percent below what experts recommend for your income level” creates concrete guidance.

Visual feedback can be particularly powerful. The Ambient Orb that glows red during high energy use reduced consumption by 40 percent. Warning lights for air conditioner filters prevent expensive breakdowns. Dashboard indicators showing real-time fuel efficiency influence driving behavior. The key is making invisible consequences visible at the point where decisions are made.

8. Test, Measure, and Iterate Your Choice Architecture

The authors emphasize that even well-intentioned nudges can fail or backfire. The only way to know what works is through systematic testing and measurement. Organizations should adopt an experimental mindset, trying different approaches and rigorously evaluating results.

The Charlotte, North Carolina school system discovered that simplified information sheets doubled the weight parents placed on school quality measures when choosing schools. The finding came from a randomized experiment comparing outcomes for parents who received detailed information versus those who got streamlined fact sheets. This kind of testing should become routine for any significant choice architecture intervention.

A/B testing, now standard in digital product development, applies equally to choice architecture in other domains. Try different default contribution rates for retirement plans and measure enrollment and satisfaction. Test various ways of presenting health insurance options and track which leads to better choices. Experiment with different framings of energy conservation messages and measure actual consumption changes.

The measurement should focus on actual outcomes, not just immediate responses. Did people who were automatically enrolled in retirement plans later opt out? Did simplified information lead to better long-term satisfaction with school choices? Did the energy conservation nudge reduce consumption sustainably or only temporarily? Long-term follow-up distinguishes truly effective interventions from those that produce short-lived effects.

Organizations should also remain humble about their ability to predict what will work. The Swedish government’s elaborate effort to encourage active choice in retirement accounts largely failed as people found the decisions overwhelming. Maine’s intelligent assignment system for Medicare beneficiaries worked far better than random assignment. Success requires testing assumptions rather than relying on intuition.

9. Maintain Transparency and Respect for Autonomy

The libertarian component of libertarian paternalism demands that nudges preserve freedom and avoid manipulation. The authors propose a “publicity principle”—organizations should be willing and able to publicly defend any nudge they implement. If you would be embarrassed if people knew how or why you were influencing their choices, that’s a strong signal you’ve crossed ethical lines.

Transparency means being open about both methods and motives. When Illinois promotes organ donation by showing that “87 percent of adults believe registering is the right thing to do” and “60 percent of adults are registered,” these are transparent social influence attempts. The same information appears on a public website for anyone to verify. Citizens can judge whether they want to be influenced by these norms or resist them.

In contrast, subliminal advertising—even for beneficial goals—violates the publicity principle because influence occurs below conscious awareness. People cannot knowingly consent to or resist manipulation they don’t perceive. Similarly, hiding default options in fine print or making opt-out procedures deliberately confusing crosses the line from nudge to deception.

The commitment to easy opt-outs distinguishes libertarian paternalism from traditional paternalism. One-click or one-call opt-out preserves meaningful freedom. Requiring employees to hunt through complex websites or complete multiple confirmation screens to change defaults imposes illegitimate costs on those exercising their freedom. The goal should be making the recommended path easy while keeping alternatives genuinely accessible.

Organizations should also provide ways for people to give feedback on choice architecture and suggest improvements. Retirement plans might survey participants about their experience with automatic enrollment. Consumer products could invite suggestions for better defaults. This kind of engagement respects user autonomy while generating valuable information for improving the system.

10. Recognize That One Size Does Not Fit All

While defaults help people who are busy, confused, or indifferent, they necessarily choose one path as primary. The authors acknowledge that diverse populations have diverse needs, and good choice architecture accommodates variation. The solution is providing an easy default path while making alternatives genuinely accessible.

For retirement plans, this means offering a high-quality default fund while allowing sophisticated investors to customize portfolios. For Medicare Part D, it means intelligent assignment based on prescription history while preserving the right to choose differently. For organ donation, it might mean presumed consent while making it completely straightforward to opt out.

The challenge is balancing simplicity for most users with flexibility for those with specific needs. Healthcare plans might offer three options (low, medium, high coverage) for most employees while providing detailed customization tools for the minority who want them. Retirement plans could have two tiers: a simple choice among three lifestyle funds for most people, and a full menu of options for those who want more control.

Technology enables increasing personalization of nudges. Instead of one default for everyone, systems can use information about individual circumstances to suggest personalized recommendations. A retirement plan might recommend different contribution rates based on age, income, and current savings. A health insurance portal could suggest plans based on actual medical needs and prescriptions. The key is ensuring personalization genuinely serves user interests rather than exploiting personal information for profit.

Conclusion: The Choice Architecture Revolution

“Nudge” represents more than a collection of clever techniques for influencing behavior—it offers a fundamentally different way of thinking about choice, policy, and organizational design. By recognizing that humans are not the rational actors of economic theory but predictable, error-prone beings navigating complex decisions, the book provides a framework for helping people without restricting their freedom.

For leaders and entrepreneurs, the implications are profound. Every organization is already doing choice architecture, whether intentionally or not. The question is whether that architecture is thoughtfully designed to help users or accidentally designed to create confusion and poor outcomes. From retirement plans to product interfaces, from healthcare options to environmental conservation, the principles in “Nudge” can dramatically improve results while respecting autonomy.

The book’s enduring contribution is demonstrating that the sterile debate between unfettered free choice and heavy-handed paternalism presents a false choice. By carefully designing environments where decisions are made—while preserving freedom and maintaining transparency—we can help people make better choices as judged by their own standards. That insight has already influenced governments, corporations, and organizations worldwide, and its relevance only grows as decisions become more complex and consequential.