Table of Contents

Every day, leaders across industries face critical moments where decision-making determines success or failure. Yet despite access to unprecedented information and analytical tools, many decisions still go wrong. The problem isn’t lack of data—it’s understanding how our minds actually process choices and implementing structures that compensate for our cognitive limitations.

The Two Faces of Decision-Making: How We Should Choose vs. How We Actually Choose

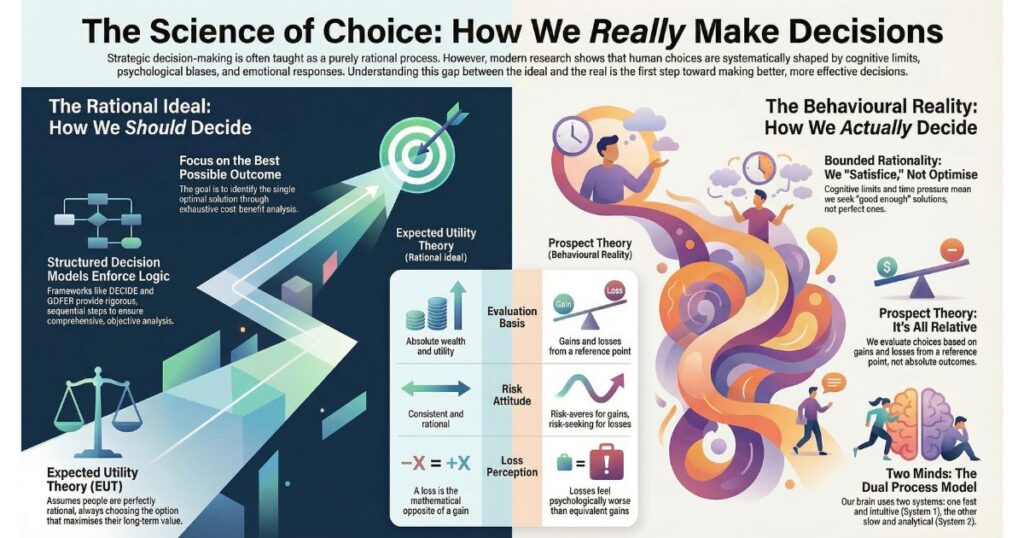

Decision-making in organizations exists at the intersection of two conflicting philosophies. Classical economic theory presents the ideal: rational actors evaluating options based on fixed preferences and objective probabilities, always maximizing a defined utility function. This Expected Utility Theory serves as the benchmark for measuring decision quality.

Reality, however, tells a different story. Behavioral economics reveals that psychological biases systematically influence perception and choice. Prospect Theory doesn’t concern itself with theoretical optimums but rather with predicting actual, observed behavior. This tension between rational optimization and behavioral reality forms the foundation of modern strategic decision-making.

The distinction matters because effective decision-making requires acknowledging this gap. Organizations that operate under the assumption of perfect rationality design processes destined to fail when confronted with human psychology.

The Critical Foundation: Framing Your Decision Correctly

Before any analysis begins, decision-making success hinges on one crucial step: properly framing the problem. Managers must ensure the issue is meticulously analyzed and clearly defined, obtaining agreement from all stakeholders on what problem is being solved. An ill-formed question inevitably produces the wrong solution, regardless of how sophisticated the subsequent analysis.

Equally important is structuring the decision team. Leaving role assignment to chance risks team members self-assigning functions in undesirable ways. Without upfront clarity on roles and formal decision-making methods, processes typically default to consensus—a mechanism that leads to less thorough evaluation and inhibits creative solutions.

For organizations serious about decision-making quality, structured frameworks provide essential rigor. The DECIDE Model offers a six-part sequence: Define the problem, Establish all criteria, Consider all alternatives, Identify the best option, Develop an implementation plan, and Evaluate the solution. The GOFER Model emphasizes exhaustive evaluation through Goals clarification, Options generation, Facts-finding, consideration of Effects, and Review.

Understanding Decision Types: Strategic, Tactical, and Operational

Not all decisions require the same approach. Decision-making effectiveness depends on matching analytical rigor to decision type. The fundamental distinction is between programmed and non-programmed decisions. Programmed decisions are routine, recurrent issues handled efficiently using established procedures. Non-programmed decisions address unique, complex situations requiring executive judgment and creative thinking—like developing new financial products or navigating unprecedented market changes.

Decisions also exist in a strategic hierarchy. Strategic decisions focus on long-term direction and organizational adaptability. Tactical decisions involve implementing chosen strategies. Operational decisions manage daily activities and efficiency. Each level demands different decision-making frameworks and timeframes.

The Power of Sequential Analysis: PESTEL Before SWOT

Effective strategic decision-making requires comprehensive environmental assessment. Two critical tools serve distinct but complementary roles, and their sequence matters enormously.

SWOT Analysis provides an introspective, tactical snapshot, focusing on internal capabilities and shortcomings combined with immediate external threats and opportunities. It’s indispensable for short-term planning and competitive analysis.

PESTEL Analysis provides a macro-environmental lens, assessing Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal factors. It offers the broader, long-range view necessary for understanding massive external impacts.

For long-term strategic decision-making, the evidence mandates sequential application: PESTEL must precede SWOT. PESTEL defines the unchangeable market trends and external forces, effectively setting operational boundaries. SWOT then determines how the organization can respond most effectively based on internal strengths and weaknesses. This combined approach transforms strategic decision-making from general assessment into context-dependent analysis anchored in both macro-reality and internal capability.

Why We Satisfice Instead of Optimize

The concept of Bounded Rationality fundamentally revises perfect economic rationality by accounting for human constraints. Decision-makers are limited by problem difficulty, finite cognitive capacity, and time pressure. Given these realities, human behavior cannot be accurately approximated by theories requiring full optimization.

Instead, individuals act as “satisficers”—they seek decisions that are satisfactory and meet adequacy criteria rather than undertaking complete cost-benefit analysis to identify the mathematically optimal choice. This perspective is crucial because perfectly rational decisions are often impractical due to real-world complexity and scarce computational resources.

The Three Pillars of Prospect Theory

Prospect Theory operationalizes Bounded Rationality by defining systematic ways human valuation deviates from the ideal. Three principal ways structure preferences differently from expected utility:

Reference Dependence: Value isn’t determined by absolute final wealth. Instead, it’s calculated relative to a neutral reference point—typically the current state—and defined purely as gains or losses from that point.

Loss Aversion: This represents Prospect Theory’s most profound discovery: losses hurt psychologically much more than equivalent gains feel good. This asymmetry means decision-makers are generally risk-averse when facing potential gains but become risk-seeking when facing potential losses.

Probability Weighting: Humans systematically distort objective probabilities, overreacting to small probability events like rare disasters while underreacting to large probabilities. This distortion further complicates rational risk assessment.

The Two Systems Driving Every Decision

Decision-making arises from two distinct cognitive systems. System 1 is fast, automatic, effortless, emotional, and based on experiential processing. It relies on heuristics and patterns for immediate, intuitive judgments. System 2 is slow, deliberate, conscious, analytical, and requires significant intentional effort for complex problem-solving and rigorous evaluation.

While conceptually distinct, these systems are interconnected, with emotional output from System 1 informing System 2 logic. However, their dynamic relationship is heavily influenced by context. Cognitive load—high stress or time constraints—actively fosters intuitive System 1 thinking. When constrained, individuals resort to heuristics and prioritize initial responses, overriding logical analysis.

This mechanism reveals that time constraints don’t merely reduce efficiency—they systematically shift decision-making from calculated rationality toward biased reality. Critically, System 2 is disproportionately responsible for reasoned, future-oriented planning, while System 1 is optimized for immediate responses. This inherent conflict between System 1’s present bias and System 2’s strategic foresight constantly threatens long-term organizational value.

The Heuristics That Hijack Your Decisions

Heuristics are efficient mental shortcuts that simplify complex information processing, allowing rapid decision-making. However, they introduce systematic errors known as cognitive biases.

The Availability Heuristic causes individuals to gauge event probability based on how easily examples come to mind. Recent, vivid, or easily recallable events get overweighted in likelihood assessments, leading to decisions based on salient, isolated cases rather than comprehensive data.

Anchoring and Adjustment involves over-relying on the first information encountered and failing to sufficiently adjust subsequent judgments away from that starting point.

The Representativeness Heuristic classifies events based on how closely they resemble prototypes or stereotypes, often leading to incorrectly finding causal relationships between things that merely look similar.

The Most Dangerous Biases in Professional Decision-Making

Several pervasive biases consistently undermine decision-making quality in professional environments:

The Sunk Cost Effect drives continued resource allocation to clearly failing projects, motivated by the desire to justify prior expenditure and avoid admitting failure.

Status Quo Bias creates inherent preference for existing conditions. People stick to default options because they’re perceived as safer than initiating change.

Outcome Bias judges past decision quality solely by eventual results, completely ignoring the analysis quality and information available when the decision was originally made.

Confirmation Bias drives people to seek out, interpret, and pay attention only to information confirming pre-existing beliefs. This significantly limits openness to contradictory information and hinders critical thinking.

The Surprising Truth About Emotion in Decision-Making

Modern research has established that emotions are crucial components of rational decision-making, not mere impediments. Without emotional markers to motivate and guide us, choice becomes virtually impossible. Emotions serve as vital signals, acting as a compass drawing attention to issues aligning with core values.

However, emotional influence is moderated by intensity. High-stakes environments and high-intensity emotions can activate the brain’s limbic system, overriding rational thought capacity. This emotional surge results in knee-jerk decisions that feel correct instantaneously but prove detrimental long-term.

The Somatic Marker Hypothesis explains this integration. Visceral feelings associated with past emotional outcomes strongly influence subsequent decision-making, especially under uncertainty. These markers allow the brain to anticipate expected bodily changes, providing rapid, unconscious signals that guide behavior. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex plays a critical role in value processing and emotion regulation. Disruption severely impairs long-term decision-making, as demonstrated by subjects performing poorly on gambling tasks. This neural integration of value processing and emotion regulation provides a mechanistic explanation for loss aversion: the anticipation of negative feelings creates a powerful, disproportionate signal driving decision-makers to avoid losses, even when economically irrational.

When Groups Make Decisions: The Promise and Peril

Group decision-making quality often differs significantly from individual members’. Groups inherently possess a diversity dividend, benefiting from wider experiences, information sources, and varying perspectives, particularly when composed of heterogeneous members. Groups typically perform above their average member level, especially when necessary information and skills are distributed among several people.

However, groups frequently suffer from process loss, meaning final decision quality falls below the single best individual member acting alone. This decrease results from coordination issues, social dynamics, or simply averaging individual contributions.

A key pathological outcome is the confidence-accuracy paradox: groups generally exhibit greater confidence than individuals. This confidence often masks underlying flaws, leading highly confident groups to make disastrous decisions.

The Groupthink Trap

Groupthink represents a phenomenon where collective pursuit of consensus and unity suppresses critical thinking and realistic appraisal of alternatives. It’s driven by high group cohesiveness, structural faults like insulating the group from outside opinions, and situational context such as high stress.

Symptoms include illusions of invulnerability creating excessive optimism, rationalization of decisions to ignore warnings, self-censorship where members suppress personal doubts, illusion of unanimity, and “mindguards” who shield the group from contradictory information.

Prevention necessitates active, structural intervention by leadership. Leaders must assign every member the explicit role of critical evaluator, deliberately avoid expressing opinions when assigning tasks, and absent themselves from many meetings to mitigate excessive influence. Organizations must mandate rigorous examination of all alternatives and require groups to seek external checks, including discussing ideas with trusted outsiders and inviting external experts to challenge assumptions.

Structured Techniques for Better Group Decision-Making

To maximize the diversity dividend while minimizing process loss, structured methodologies deliberately impose System 2 discipline on group interaction.

The Nominal Group Technique is a highly structured, face-to-face process ensuring every participant’s input is heard and considered, preventing anchoring and self-censorship. The stages are: silent generation of ideas, verbatim sharing without discussion, clarification of all recorded ideas, and finally quantitative voting to determine weighted priorities. By enforcing individual, silent idea generation, this technique compels analytical thought before social pressures interfere.

The Delphi Technique achieves consensus through anonymity, utilizing multi-stage questionnaires with feedback cycles rather than face-to-face discussion. Preserving participant anonymity eliminates direct social pressure, allowing honest critiques from large, geographically dispersed groups over longer periods.

Advanced Tools: Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis

Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis provides a robust, transparent framework for strategic decisions involving multiple, often conflicting objectives. It’s a practical application of Bounded Rationality, offering a rigorous path to satisfactory, auditable outcomes.

The process enforces systematic, analytical rigor through defined steps: structuring the decision problem, specifying relevant independent criteria, measuring alternatives’ performance, scoring and weighting criteria by importance, and ranking alternatives by multiplying scores by weights. The process culminates in mandatory sensitivity analysis, examining ranking stability against potential variations in initial weights and scores. This ensures decisions are robust and not overly dependent on fine-tuned subjective inputs.

Quantifying Risk with Decision Trees

Quantitative tools are essential for evaluating outcomes under uncertainty. Decision Trees are visual, branching models outlining all potential outcomes, costs, and consequences, employed in operations, budget planning, and project management.

The core analytical power derives from calculating Expected Monetary Value. This quantifies risk by assigning probability and monetary value to each potential outcome. The value multiplied by estimated probability provides the expected financial value, allowing managers to compare alternatives objectively based on quantified risk profiles.

For instance, evaluating a renovation project with a best-case cost of fifty-five thousand dollars at sixty percent probability and worst-case of seventy-five thousand dollars at forty percent probability yields an expected value of sixty-three thousand dollars. This structured quantification provides a powerful metric resisting fast, emotional System 1 judgment while providing basis for financial due diligence.

The Art of Cognitive Debiasing

Cognitive debiasing is the intentional effort to mitigate systematic judgment errors. The fundamental mechanism is metacognition and decoupling—deliberate disengagement from intuitive judgments. The goal is enforcing analytical processes to verify initial impressions, a crucial executive override function.

Since cognitive load and time constraints promote intuitive errors, effective debiasing must involve adjusting the decision environment to allow slow, effortful System 2 processing.

Effective strategies include slowing down to allocate sufficient deliberation time, preventing premature conclusions from rapid processing. Structured data acquisition implements requirements for deliberate collection, avoiding spot diagnoses by forcing consideration of less obvious yet relevant facts. Actively seeking contradictory evidence neutralizes destructive confirmation bias by soliciting feedback, engaging in healthy debate, and formally searching for conflicting data. Recalibration cultivates skepticism and implements processes for adjusting risk assessments when additional risks are anticipated.

Building a Decision-Quality Audit Framework

To ensure accountability and continuous improvement, organizational decision evaluation must move beyond judging based on outcomes. A robust audit framework must verify process quality. This involves checking procedural adherence: confirming decision-makers applied decoupling steps, sought external critical review, and utilized structured analytical frameworks appropriate for complexity and stakes.

By focusing on process fidelity, organizations create a culture where rational methodology is rewarded, independent of the variable influence of chance.

The Path Forward: Institutionalizing Rigorous Decision-Making

Strategic decision-making is defined by necessary tension between pursuing rational optimums and accepting behavioral realities. The primary challenge isn’t lack of information but the intrinsic cognitive architecture that defaults to rapid, intuitive processing whenever resources are scarce.

The most crucial recommendation for improving strategic outcomes is institutionalizing System 2 rigor through structural and procedural mandates. Organizational leadership must strictly enforce systematic problem definition and explicitly clarify roles, responsibilities, and decision-making methods. For long-term decisions, require sequential execution of PESTEL followed by SWOT analysis, ensuring strategy formation is first grounded in macro-environmental constraints before assessing internal capabilities.

Cognitive debiasing should not be viewed as training but as structural protocol. All high-stakes decisions must be subjected to mandated procedural checks, including structured data acquisition, formal requirements to solicit contradictory evidence, and application of quantitative methods and rigorous scoring models.

Decision-makers should actively manage the ambient environment by reducing unnecessary cognitive load and time pressure. Since stress and urgency activate System 1 bias, allocating sufficient, unconstrained time for deliberation is the most fundamental mechanism for enabling high-quality strategic thought.

Finally, adopt a decision-quality audit framework evaluating process fidelity rather than judging success solely on eventual outcomes. This standard mitigates outcome bias and reinforces the value of disciplined analysis.

The science is clear: exceptional decision-making isn’t about being smarter—it’s about building systems that work with, rather than against, human cognitive architecture. Organizations that embed these principles into their culture don’t just make better decisions—they create sustainable competitive advantage through superior strategic thinking.